Talents from hololive production are loved by fans all over the world and to bring their charm to audiences beyond language and cultural barriers, our Localization Team works tirelessly behind the scenes.

So what exactly does “localization” involve beyond simple translation? In this article, we take a closer look at what the Localization Team does and share the interview we had with two of its members - our English and Indonesian specialists.

The Wide-Ranging Work of Localization

Content localization refers to the process of adapting content created in one country or region so it resonates naturally with users in another language or cultural setting: it is more than simply translating words. The role of our Localization Team requires an understanding of local customs, cultural context, regulations, and values, and adjusting expressions so the overall message feels authentic and reaches the audience effectively.

Our Localization Team is made up of around ten members, covering a wide range of languages – English, Indonesian, Spanish, Korean, and both Traditional and Simplified Chinese. Each language has its own in-house specialist, who also works with a network of freelance translators. The team is also supported by our subtitle production staff, who take care of technical tasks such as “spotting,” the process of working out when subtitles should appear on screen.

Examples of Content We Localize

- Videos on the official channel (including the 3D animated series “holo no graffiti” (hologra), variety segments, short videos, etc.)

- Music video lyrics

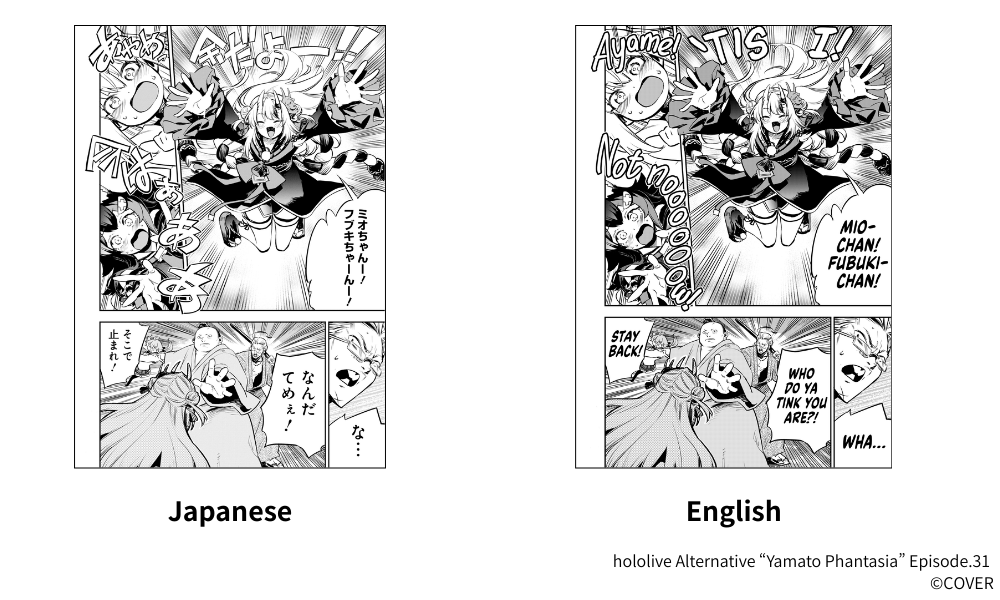

- The manga series “hololive Alternative” (including “Yamato Phantasia,” “Vesta de Cooking,” and “Underworld Academy Overload!!”)

- 3D live performances

- Subtitles for Blu-ray versions of real-life concerts

- Official website content

- Talent voice pack content

- Social media posts

- Individual talent projects (e.g., “Legend of Polka” by Omaru Polka; members-only four-panel comics of Tsunomaki Watame, etc.)

<Example> How We Localize hologra

1.Subtitle staff does the spotting for the episode

2.A script is prepared in a spreadsheet ready to be translated

3.Translators for each language are assigned to input their translations(English, Spanish, Indonesian, Korean, Chinese, Thai subtitles)

4.Localization staff for each region review and refine the translations

5.Once everything is checked, the finalized version is used to create the subtitles

<Example> How We Localize hololive Alternative Manga

1.Japanese dialogue and sound effects are translated by localization staff or by external translators, who create the initial draft

2.The translated text is inserted directly into the manga panels

3.The Japanese and translated versions are reviewed side by side, and necessary adjustments are made

4.Finally, our team carries out a Linguistic Quality Assurance check to ensure there are no typos or missing lines/sound effects.

From NARUTO to GTO: How Entertainment Sparked Journeys to Learning Japanese

Quietly supporting COVER’s global expansion behind the scenes are two members of the Localization Team with whom we sat down for this interview: team leaders Sriram Gurunathan (also known as Ram) and Natalia Solichin, who oversee English and Indonesian respectively.

――When did you both come to Japan, and when did you start working at COVER?

I came to Japan from Indonesia seven years ago. After spending a few years studying Japanese, I worked at a gaming company where I handled translation and localization for social games before joining COVER in 2024.

I arrived in Japan later than Natalia. I’m originally from India, and I began working with COVER around 2019 as a freelance translator from my home country. I was set to join the company in 2021, but the pandemic made it impossible to travel. Once I finally received permission to enter Japan, I moved here and officially joined the company in May of 2022.

――Since you’re from India, is Hindi your first language?

No, my first language is English. In India, English is one of the official languages, and many school curriculums are taught entirely in English, including mine.

India has more than 450 regional languages – some similar to one another and others completely different. Even distances as close as Tokyo and Kanagawa can see people speaking entirely different languages, not just different dialects. As my father’s job required us to move frequently, I spent my childhood relocating to all kinds of places and each time we moved, I had to learn a new language. Looking back, I think that experience really strengthened my ability to pick up languages.

――What inspired you both to start learning Japanese?

Japanese pop culture is hugely popular in Indonesia. I grew up watching manga and anime like “Doraemon” and “NARUTO,” and that naturally made me curious about the country they came from. At one point, I even tried playing a NARUTO game without understanding any Japanese and as I kept playing, I slowly started to recognize katakana – mainly because the character names were written in katakana.

――That’s very true. The first names of Naruto, Sasuke, Sakura, and Hinata all appear in katakana, don’t they?!

Exactly. That’s actually how I ended up learning Japanese: I started with katakana before moving on to hiragana, and then kanji.

I’ve never met anyone who learned Japanese in that order! Most people start with hiragana, then katakana and after that kanji.

It probably is a little unusual (lol). Even after that, I continued consuming other Japanese works that had been translated into Indonesian, but there were no translated versions of things such as doujinshi (self-published works), and there were some that I really wanted to read, so that pushed me to start studying Japanese more seriously.

That’s actually a pretty common pattern among overseas otaku learning Japanese (lol). About ten years ago, it was normal to wait six months to a year for the English versions of Japanese content to come out, so a lot of fans started learning Japanese simply because they wanted to read or watch things as soon as they could.

In my case, the first Japanese show I ever watched was GTO, the one starring Takashi Sorimachi. I watched it with English subtitles and got completely hooked. After that, I spent the next seven years devouring all kinds of Japanese content and eventually, I could understand about 70 percent of it and that’s when I decided to start studying the language more seriously.

Bringing Out Each Talents’s Charm Through Translation

――What are some of the challenges you face when localizing Japanese content?

One challenge is translating expressions that are commonly used in Japanese but don’t exist in Indonesian. For example, phrases like “yoroshiku onegaishimasu” or “otsukaresama desu” don’t have direct equivalents. So I adjust them depending on the context – sometimes as a greeting, or sometimes as a message of appreciation.

Right. Instead of translating the words literally, we focus on what the phrase means in that specific situation and choose the wording that fits best.

That’s right. Another challenge is translating Japanese onomatopoeia. Manga often uses sound effects as if they were dialogue, like “rero-rero” for licking or “sara-sara” for the sound of writing. But in Indonesian, those kinds of onomatopoeia feel very unnatural. So in those cases, I usually rewrite them as descriptive sentences instead of trying to recreate the sound.

When I first started translating, I remember wondering what “jii-” means in expressions such as “jii-to miru” (staring intently). Japanese onomatopoeia can be tricky even when translating into English.

――Content from hololive production seems especially challenging to localize, since each talent has their own unique way of speaking and distinct character.

That’s true. hologra, in particular, is a comedy-style show with lots of wordplay in Japanese, so localizing it can be quite tough.

Comedy… I’m not sure that’s the right word (lol). To me, it feels more like “denpa-kei (nonsense humor)” – the kind of charm that comes from things being slightly nonsensical. For example, the maid cafe episode was absolute chaos.

――You’re talking about the “U Maid?” episode, right?

It was the episode where Shirakami Fubuki, La+ Darkness, and Omaru Polka – classic old-school otaku types – dote on FUWAMOCO (Fuwawa Abyssgard and Mococo Abyssgard), who are dressed as maids. The whole thing was filled with otaku slang and internet memes like “megane-kui, “shomo-suru,” and “kiri.” There was no way to translate them literally, so I replaced them with English slang and memes that would convey a similar vibe.

For the Indonesian subtitles, I use Indonesian memes instead.

――So, even though the wording wasn’t exactly the same as the original Japanese, you chose English or Indonesian expressions that still have that slightly old-school, otaku-like feel. That sounds like quite a challenge.

Surprisingly, that part was actually pretty easy for me. I’m an old-school otaku myself, so all the phrases just came naturally (lol). Translating otaku terms comes with its own set of challenges, though. Take “tsundere,” for example. In English-speaking otaku circles, the word “tsundere” is already widely used, so I understand why many people think we should simply keep it as is. But as an official localization team, we want the content to be enjoyable for fans who aren’t necessarily familiar with otaku culture, which is why I intentionally choose words that are easier for a broader audience to understand.

――How would you translate it?

There are expressions like “hot and cold,” but that isn’t really well-received among otaku. They’ll say, “Why does it start with the ‘dere (hot)’ part?” since the whole point of ‘tsundere’ is that someone goes from feeling ‘tsun (cold)’ to ‘dere (hot)’. ” So when I translate it, I adjust the wording each time depending on the context.

“Tsundere” is also tricky to translate into Indonesian. Sometimes I adapt it depending on the context, and other times I add a brief note explaining what “tsundere” means.

Adding explanations is another option too. But we’ve been doing it less and less lately because, with entertainment content, it’s important that people understand things instantly, so we try not to make it feel too much like studying.

Exactly. I think it’s all about finding the right balance so the subtitles remain easy to read as part of the content. Indonesian subtitles tend to be longer than those in Japanese or Chinese, so they can easily take up more space. But if viewers are too busy reading the subtitles to enjoy the content itself, that defeats the purpose. So while keeping translations accurate, I try to keep them as short as possible – ideally within two lines.

As the official localization team, we also see it as our role to keep each talent’s image consistent across different regions. In the VTuber community, fans often add their own translations to clipped videos, which creates a culture of many different interpretations. That means a single phrase can end up with multiple translations depending on who’s doing it. For example, take the unique greeting “Tis’ I!” (“Yo dayo~”) used by Nakiri Ayame. Everyone has translated it differently, so by providing an official translation through hololive production’s content, we’re able to offer something that fans can consider a standard translation.

――That makes sense. The words you choose in translation can really shape how a character comes across – cute, serious, playful, and so on. That’s a big responsibility.

Exactly. That’s why we research each talent carefully, including watching their streams, so we can produce translations that feel natural and stay true to their personality.

Sharing the Same Joy Across Languages and Cultures Through Localization

――Is there a project that left a strong impression on you?

For me, it would be the hologra graduation episode for Nanashi Mumei, titled “Memories I Will Not Forget.” It’s the episode where Nanashi Mumei visits other talents before graduating, and there’s a scene where Anya Melfissa from hololive Indonesia prepares a whole stack of stone tablets covered in ancient writing just so Nanashi Mumei can get to know her better. In the scene, Nanashi Mumei reads the ancient inscriptions with ease, which really impresses everyone around her, but in the original script, those “ancient characters” were just random strings of text. I felt that instead of having her read out meaningless letters, having her read the inscriptions in Javanese would give more context to the tablets in relation to Anya’s lore and make the moment feel more authentic.

When I pitched this idea, they decided to run with it. I also recorded the Javanese lines for reference and shared them with Nanashi Mumei, who used them during the actual recording. After the episode was released, seeing that fans had noticed and reacted with comments like, “Nanashi Mumei is speaking Javanese!” and “They even localize such small details like that?” made me really happy.

One project that has really remained with me was when I localized the lyrics for Hoshimachi Suisei’s “Stellar Stellar” music video. I translated the English subtitles so they could actually be sung along with the melody, which was quite a challenge. Hoshimachi Suisei once mentioned that she wrote the lyrics after extensively reading The Little Prince, so I wanted the English version to subtly reflect that. Not by stating it outright, but in a way that would make attentive listeners think, “Is this inspired by The Little Prince?” Striking that balance was tricky, but taking a deep dive into the lyrics and searching for the best possible wording made the whole process both challenging and enjoyable.

Translating Japanese song lyrics is pretty difficult, isn’t it?

It is. Even when the lyrics are abstract or don’t specify a subject, they still make sense in Japanese. But that doesn’t work the same way in English or Indonesian – we have to decide who the lyrics are referring to or to whom something belongs. I struggle with that every single time, but music is something people can enjoy regardless of language – it’s universal. And that’s exactly what we aim for as a localization team. So I really want to keep putting energy into lyric localization for music videos moving forward.

ーーHave you noticed any differences in how fans from different countries react to content?

Our job in localization is to minimize those differences. Even if the language they receive is different, the goal is for fans everywhere to have the same experience and the same sense of enjoyment. If there’s still a gap in that sense, it means we haven’t done our jobs well.

Localization is all about making content feel just as natural in different languages and cultures. That’s the challenging part, but it’s also what makes the work so enjoyable.

――Lastly, what do you find most rewarding about working in localization at COVER?

I’ve spent countless hours enjoying Japanese entertainment, and I’m genuinely grateful for all the great moments it has given me. Now, being able to help share that same content with fans around the world feels deeply rewarding.

At COVER, there’s a strong commitment to global expansion, and the Localization Team plays a key role in that. That certainly comes with some added pressure, but when a localization project turns out well, the sense of accomplishment is huge.

It really does come with a lot of responsibility. Since each language has just one person in charge, you feel almost like the representative for that language within COVER. For anyone who wants to take on meaningful, high-impact work, I think this is an incredibly rewarding place to be.